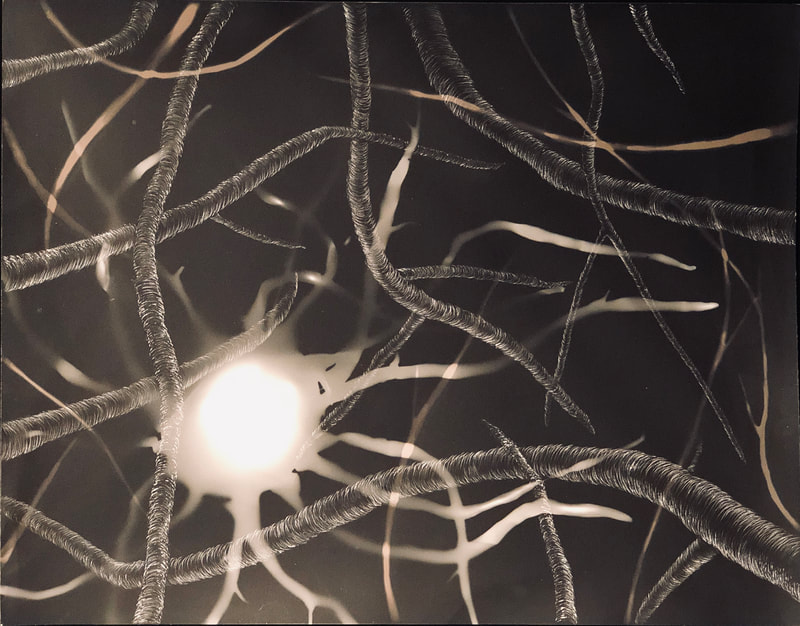

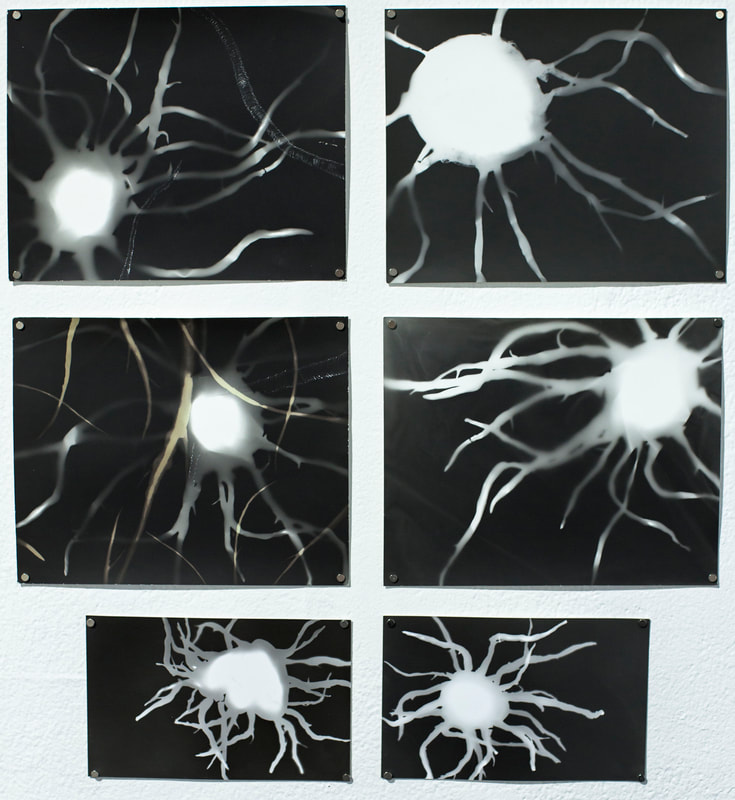

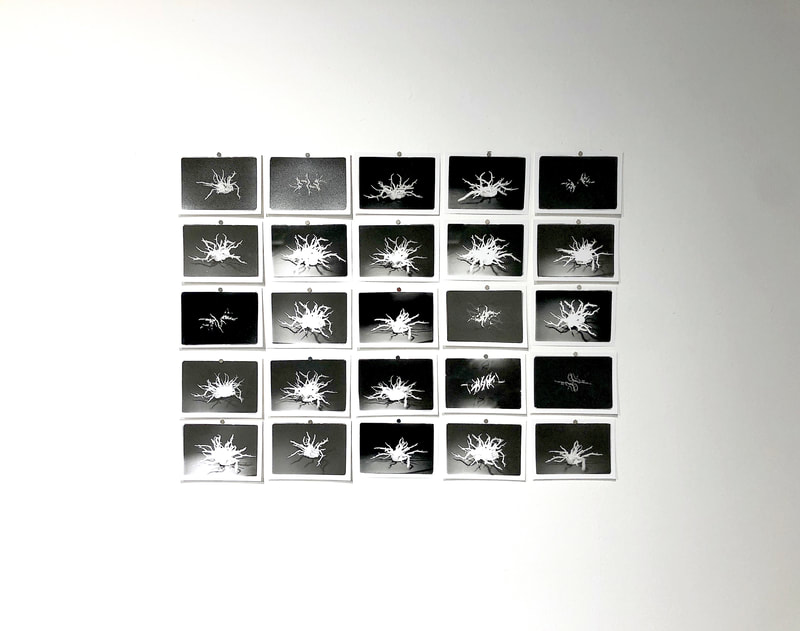

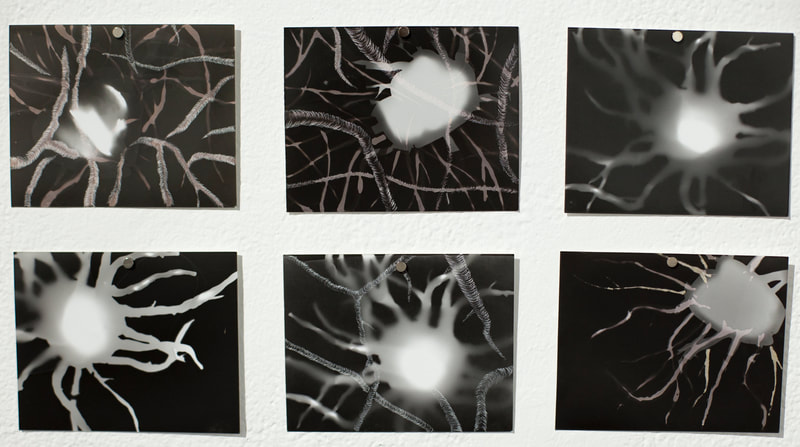

Inundated

|

I researched the anatomical origins of anxiety in the brain and learned about the amygdala. The amygdala is responsible for our fight or flight responses and there were found to be more connections stemming from the amygdala in people who have anxiety than those without. I used the high contrast of black and white photography to depict the amygdala. Using a combination of bleach and blade engravings, I wanted the connections to take over the pieces. It was important to me that the connections visually overwhelm the work to convey the feelings I have when dealing with anxiety.

|

All content © Michelle Drummy 2019 unless otherwise specified.